Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

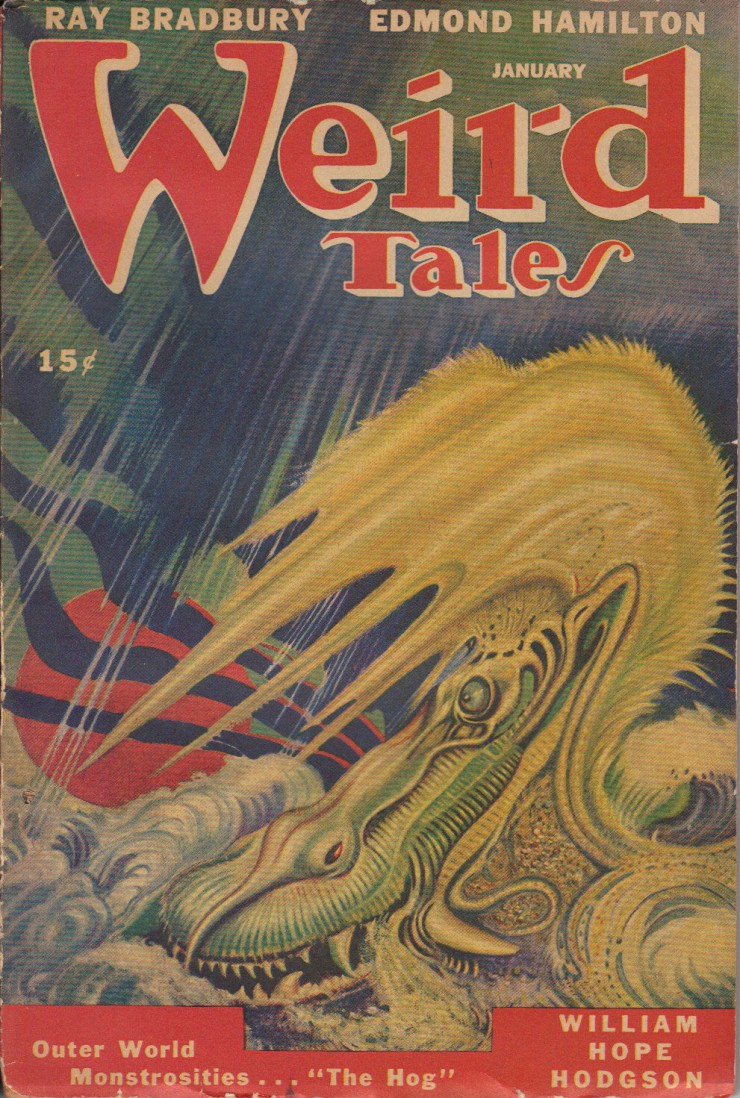

Today we’re looking at William Hope Hodgson’s “The Hog,” first published in Weird Tales in 1947 but certainly written much earlier since the author died in 1918. Spoilers ahead.

“I’ve heard it. A sort of swinish clamouring melody that grunts and roars and shrieks in chunks of grunting sounds, all tied together with squealings and shot through with pig howls. I’ve sometimes thought there was a definite beat in it; for every now and again there comes a gargantuan GRUNT, breaking through the million pig-voiced roaring—a stupendous GRUNT that comes in with a beat. Can you understand me?”

Summary

Beside a cozy postprandial fire, narrator Dodgson and other friends listen to Carnacki the Ghost Finder’s tale of a recent catastrophic experiment. Dr. Witton, a decent but intractably practical physician, told Carnacki about a patient called Bains. Carnacki thinks Bains might have a gap or flaw in the “protection barrier” which would otherwise spiritually “insulate” him from the “Outer Monstrosities.”

Carnacki invites Bains to visit. Bains describes dreams so real they seem like actual experiences. In them he wanders a “deep, vague place,” surrounded by unseen horrors, a “hellplace” which some “sudden knowledge” insists he escape. He fights to wake before he turns the corner beyond which a soul-destroying monster waits. He seems to wake, sees his room around him, but the “real” Bains remains in the hellplace. Rigid in bed he makes an agonized effort and reunites body and soul. Then, as he lies exhausted, he hears from enormous depths piggish grunts and squeals and howls. At regular intervals, a stupendous GRUNT punctuates the swine chorus. Is he bound for a madhouse, or can Carnacki help him?

Carnacki’s willing to try—though he warns Bains of the danger, and the need for absolute obedience. He prepares his experimenting room with his new “spectrum defense”: seven glass vacuum circles, concentric, laid on the floor. The outermost produces red light, the innermost violet, with orange, yellow, green, blue and indigo circles in between. Carnacki controls the lighting of the circles with a keyboard and can try out many combinations. Red and violets, he knows, are most dangerous, as they have a “drawing” or focusing effect on forces, whereas blue is “God’s own” color. (He must use the spectrum defense with Bains as he wants both to draw energies and defend against them, whereas his electric pentacle will only defend.)

Bains confesses with shame what he omitted before—he grunts along with the pigs while recovering from a dream bout. Carnacki outfits them both with rubber suits and has Bains lie on a glass-legged table within the spectrum defense. He attaches an electrode band to Bains’s head, and to a glass disk composed of intricately twined vacuum tubes. Now Bains must concentrate on the pig noises he hears when waking, but for God’s sake, he mustn’t fall asleep.

Carnacki uses a modified camera and phonograph to capture Bains’s thoughts and translate them into sound. Sure enough, he’s treated to the swine chorus and punctuating monstrous GRUNTS. Another phenomenon draws his attention—a circular shadow is forming under Bains’s table. Carnacki tells Bains to stop concentrating. But Bains has fallen asleep, and Carnacki can’t wake him, though Bains opens eyes mad with horror. Then Bains starts grunting. The shadow widens like the mouth of a black pit, into which they appear to sink even as the floor remains solid under Carnacki’s feet.

Carnacki lifts Bains but can’t carry him out of the defense, for “dangerous tensions” surround the spectrum circle in the form of a swirling black funnel cloud. Desperate, he tries to recall Bains’s wandering “essence” by pricking blood from him. Of course as the Sigsand mentions, blood also calls the Monsters of the Deep. The pit mouth spreads to fill the whole defended zone. To escape Carnacki steps between the lit violet and indigo circles, cradling the rigid Bains. Now they’re trapped between pit and funnel cloud!

The room shakes. A storm of swinish noise surrounds the stranded men, punctuated by gargantuan GRUNTS from the pit. The silence that follows presages such spiritual doom that Carnacki considers shooting Bains and himself. Down in the pit a luminous spot appears and slowly rises. It resolves into a tremendous pig-face. Meanwhile pig snouts and trotters momentarily pop out of the swirling funnel-wall, and Bains’s grunts answer the renewed chorus.

Carnacki realizes the pig-face is that of the Hog, which the Sigsand calls an Outer Monstrous One, once powerful on the earth and eager to return. With Bains as a conduit, it’s on its way!

Only a psychic message from the inscrutable “Protective Force” stops Carnacki from using his pistol. Instead he starts dragging the blue-emitting vacuum tube outward, along with Bains. The funnel cloud recedes before it. Oops, the Hog physically possesses Bains, who rushes on all fours towards its now protruding snout and eye. The blue circle traps Bains, however. He tries to shove Carnacki out of it, but Carnacki manages to dodge and tie him up with his suspenders.

The inexorably rising Hog lifts the inner violet tube and melts it. It starts lifting the indigo circle, the only defense left between it and the men. Luckily “certain Powers” are watching from afar. They send a dome of green-striped blue light which dispels Hog and funnel cloud, no problem.

Bains wakes, thinking he’s dreamt again. Carnacki hypnotizes him into a sleep from which he’s commanded to wake if he has any more such dreams. All that remains of their ordeal is the melted violet tube and damaged indigo one.

End of tale. During the question and answer session that follows, Carnacki describes his theory that Earth (and presumably other planets) are surrounded by concentric spheres of “emanations.” The Outer Circle starts about 100,000 miles off and extends five to ten million miles out. In this “Psychic” Circle reside such forces and intelligences as the Hog, which hunger for the psychic entities or souls of men. Got that? Dodgson says yes and no, but Carnacki’s too sleepy to lecture on and says good night.

What’s Cyclopean: Carnacki really likes the phrase “spiritual insulation from the Outer Monstrosities.” We do too, maybe even enough to say it twice like he does.

The Degenerate Dutch: Carnacki’s world appears to consist solely of upper crust British gentlemen—not only no women or people of other ethnicities, but no one who can’t be imagined smoking a pipe.

Mythos Making: Carnacki’s books and rituals later appear in Mythosian stories by Ramsey Campbell and Barbara Hambly.

Libronomicon: The Sigsand manuscript speaks about colors in the most ominous terms. Maybe Lovecraft had a point when he made his “color” with no reference to the everyday spectrum, because “the devil gets totally freaked out by reddish purple” isn’t the most awe-inspiring concept.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Bains’s original doctor thinks him “booked for the asylum.” Carnacki begs to differ.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

You all know that I can be pretty picky when it comes to the Mythos. However, my detached analysis goes completely out the window when it comes to Mad! Science! Mad Science Mythos just makes me bounce and declaim Capitalized Equipment Specs squeefully at my wife: The New Spectrum Defense! Dream Recording Record Players! By Jove! Carnacki announces, “I must tell you,” before imparting minute descriptions that never come up again—oh, it’s beautiful!

“There may be horrible danger.” And horrible dialogue. Wonderful, horrible dialogue. “Now, just let me fix this band on your head.”

But then, just as I’m settling in for a really good goggle-eyed rant, the tone shifts. All this absurdity at the beginning, and then imperceptibly we shift ‘til we’re standing frozen between horror and horror, listening to the rhythmic rise and fall of the swine noises. Suddenly they stop… and then… the silence trickles. Perfect. Does it seem more horrible in contrast to the joyously absurd science-ing and Carnacki’s ultra-specific measurements? Is a satanic hog worse if you know the exact dimensions of the room in which it threatens to appear?

The rising and falling rhythm of Carnacki’s fear, mirroring the pattern of swinish grunts and whines, weaves wonderfully through this part of the story. He goes from near-suicidal terror to bone-deep revulsion to that false calm where strangeness overwhelms horror. “Can you understand? I want you to try to understand.” The emotions are as precisely detailed as the measurements.

Bains, grunting and unable to wake or be woken, is creepy. So very creepy. As is the moveable, inescapable hole. The imagery is both unique and built over universal nightmares: knowing danger is coming and being unable to run, friends in grave danger who won’t awaken, that desperate thin circle between equal terrors.

When it looked for a moment as if Bains was lost to the Hog, I was really horrified—and mad at Carnacki, for missing the obvious risk of his little experiment—a worse betrayal after Bains told him how safe he felt. And mad, too, knowing he was going to survive the thing. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen that reversal before, where the knowledge that the storyteller is going to survive adds to the situation’s horror.

The story ends in a Deux ex machina. And weirdly so—Christian framing is used throughout, and yet it never occurs to Carnackie to make the sign of the cross as his book suggests. Why not? He talks about souls, but the only strategy he considers is his machine. And while his work on that machine probably buys a few crucial seconds, the Blue Rescuer comes in its own time and of its own accord. Maybe this is the world’s weirdest analogy for Calvinism?

And then… we’re back in the safety of Carnacki’s parlor for a little Q&A. Like an academic talk with soul-destroying horror in the middle. I’ve been to some of those. At story’s end, though, it’s clear that Ether and Celestial Spheres and Science! stand in for comfort and normalcy. Knowing now what lurks beyond the comfort of Carnacki’s parlor, it’s just a little harder than it was at the beginning to cackle blithely with mad glee.

Anne’s Commentary

In Supernatural Horror in Literature, Lovecraft praised Hodgson’s novels of horror on the high seas, The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’ and The Ghost Pirates, for their nautical authenticity, not surprising given Hodgson’s early career as a sailor. The House on the Borderlands (1908) featured many tropes close to Lovecraft’s heart: otherworldly forces, hybrid anomalies deep underground, a narrator who psychically travels through time and space, even witnessing the final destruction of our solar system. The Night Land (1912), set billions of years after the death of Earth’s sun, won his admiration for the potency of its macabre imagination, though like House on the Borderlands, it was tainted by “nauseatingly sticky romantic sentimentality.” Does that mean girl cooties or just generalized icky emotionality?

Too bad Hodgson died early in his literary career, victim of an artillery shell at Ypres in 1918. WWI had a way of kicking the sentimentality out of its soldiers.

Regarding this week’s hero, Thomas Carnacki, Lovecraft wasn’t much impressed: “In quality [the Carnacki collection] falls conspicuously below the level of the other books. We here find a more or less conventional stock figure of the ‘infallible detective’ type—the progeny of M. Dupin and Sherlock Holmes, and the close kin of Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence—moving through scenes and events badly marred by an atmosphere of professional ‘occultism’. A few of the episodes, however, are of undeniable power; and afford glimpses of the peculiar genius characteristic of the author.”

I wonder if Lovecraft would have considered “The Hog” one of these episodes? From what I can discover, it wasn’t published until 1947, ten years after his death. “Hog” keeps clear of the sentimental, although it’s steeped in “professional occultism” and its paraphernalia. But come on, how could Howard not have enjoyed that spectrum defense and that camera-phonograph thought-translator? Surely they’re worthy of installation in the Fictional Gadgets Hall of Fame, along with the brain-canisters of the Yuggothians and the consciousness-projectors of the Yith. The visual power of the black pit and funnel-cloud wouldn’t have left him unmoved, likewise the fine descriptions of spiritual terror in the face of Outer Monstrosities. I fear he wouldn’t have liked the literal deus ex machina of the saving blue-green dome. I don’t like it, either. Why despair over Outer Monstrosities when there are also Outer Benevolences to counter them before things get too hairy? Also, Carnacki’s cosmic scale isn’t all that cosmic. His Outer Sphere is only 100,000 miles from Earth? That doesn’t even make it halfway to the moon! And it only extends 10 million miles? The sun’s more than nine times farther off. That long denouement might also have irked him. If you’re going to infodump, do it before the Outer Monster appears. And again, Outer Monsters shouldn’t be scared off so easily. Let the Hog snack on Bains at least—he’s come all that way!

And what about that Hog and Its Thousand (Million) Piglets? I figure the entities themselves don’t really LOOK like pigs—that’s just how we humans perceive—picture forth—their tremendous greed and hunger. (Similarly, we perceive the voracious Tindalos beings as “hounds.”) Still, how innately scary is the pig image, at least for those who haven’t had run-ins with feral swine? Aren’t pigs kind of cute? Funny? All pink and cuddly? Like in Winnie the Pooh and Babe? Yet, yet, yeah, Hodgson’s Hog is pretty nasty. And the noises pigs make can be chilling. A film would have to make sure to give the Hog big old boar jowls and tusks. (I keep seeing Wilbur from Charlotte’s Web emerging from the pit, and that’s just not spiritually terrifying enough.)

They didn’t have the Sigsand Manuscript at my local library. Alas, I understand it’s only to be found among the other invented tomes in the Miskatonic University Archives; worse, they won’t lend it out to nonfictional characters. Hodgson gifted the 14th century MS to Thomas Carnacki for his protection from the semi-material Aeiirii entities and less ethereal Saiitii manifestations. It contains the Saaamaaa Ritual and mentions an Incantation of Raaaee. Obviously the author of the Sigsand had too many vowels lying around the house and couldn’t stand to throw them out. However, in an uncanny instance of great fantasists thinking alike, “Sigsand” must have read the Necronomicon, for he writes:

“…ye Hogge doth be of ye outer Monstrous Ones, nor shall any human come nigh him nor continue meddling when ye hear his voice, for in ye earlier life upon the world did the Hogge have power, and shall again in ye end.”

I shivered, instantly recalling Alhazred’s warning:

“Man rules now where [the Old Ones] ruled once; They shall soon rule where man rules now. After summer is winter, and after winter summer. They wait patient and potent, for here shall They reign again.”

Maybe the Hog with a Thousand Piglets is the Goat with a Thousand Young, after all! Ai, Shub-Niggurath! I’ll text the girls from Boras and see what they think.

Next week, Elizabeth Bear’s “Shoggoths in Bloom” offers a very different take on a Mythosian monster that rarely gets sympathy.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

“The Hog” is one of the best Carnacki stories, which admittedly isn’t saying much…

Lovecraft on Hodgson: another “Supernatural Horror in Literature” excerpt:

“Of rather uneven stylistic quality, but vast occasional power in its suggestion of lurking worlds and beings behind the ordinary surface of life, is the work of William Hope Hodgson, known today far less than it deserves to be. Despite a tendency toward conventionally sentimental conceptions of the universe, and of man’s relation to it and to his fellows, Mr. Hodgson is perhaps second only to Algernon Blackwood in his serious treatment of unreality. Few can equal him in adumbrating the nearness of nameless forces and monstrous besieging entities through casual hints and insignificant details, or in conveying feelings of the spectral and the abnormal in connexion with regions or buildings…

Mr. Hodgson’s later volume, Carnacki, the Ghost-Finder, consists of several longish short stories published many years before in magazines. In quality it falls conspicuously below the level of the other books. We here find a more or less conventional stock figure of the “infallible detective” type—the progeny of M. Dupin and Sherlock Holmes, and the close kin of Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence—moving through scenes and events badly marred by an atmosphere of professional “occultism”. A few of the episodes, however, are of undeniable power; and afford glimpses of the peculiar genius characteristic of the author.”

Weird Tales: January 1947, with August Derleth’s “The Extra Passenger”, Theodore Sturgeon’s “Cellmate”, Ray Bradbury “The Handler” and a couple of Fungi from Yuggoth: “The Familiars” and “The Pigeon-Flyers”.

Interesting if it was never published until 1947 because the description reminded me quite a bit of both “From Beyond” and “The Transition of Juan Romero”.

I feel like this story might have benefited from the author giving it a final polish. There’s rather too much pseudo-scientific mumbo-jumbo for my taste, and I found some of it difficult to follow. This is less of a problem with other Carnacki stories.

Those stories are, admittedly, not Hodgson’s best. Apparently he came up with Carnacki in deliberate imitation of John Silence in an effort to write something that would be commercially successful. For some reason a lot of little things converged to make me like this one less. Carnacki’s verbal tics, the weakly explained occult science, the deus ex machina, and even the fact that the authorial stand-in is named Dodgson. It’s like Anne naming such a character Hillsworth or Ruthanna calling a character Merys.

Hodgson seems to have had a thing about pigs. The creatures in The House on the Borderland are also swinish.

Carnacki will forever be Donald Pleasance in my head (which made him lugging Bains around hard to accept). Some 45 years ago, there was a joint BBC/PBS production called The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes, with various late Victorian detectives like Lady Molly and Max Carrados. “The Horse of the Invisible” was one of the tales, starring Pleasance as Carnacki.

Whenever scary pigs show up, I am always reminded of a short ghost story I read a while back, involving someone sleeping in an abandoned house and having terrible pig-related nightmares, first with a huge pig standing atop his bed, and later with something black, even larger and indeterminate in nature taking its place. Can anyone ID the tale?

Colored light’s magical powers has a long history, especially in quack medicine: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chromotherapy

The Hog itself is an effectively scary monster, but having Benificent Entities show up and stop It unbidden takes this out of the field of proper Lovecraftian fiction into Lumleyland, IMHO. :)

Possibly the Outer Sphere is just the horrors and monsters associated with _this_ world and humanity: maybe other inhabited planets have their own Outer Spheres and their own abominations. The Hog, scary as it is, is just a local player.

Carnacki is a bit careless: after all, in a horror story, when has the person who is to stay awake _not_ fallen asleep? At least he should have got Bains some coffee.

It occurs to me that there is a pig demon in The Amityville Horror. That’s not what Bruce is looking for @@.-@, but it was fairly creepy.

Feral pigs are dangerous and they do make some pretty scary noises. I suppose they’ve made their way into horror literature primarily through the story of the Gadarene swine. That does seem like an influence here.

I’m fine with the mad-sciencery. Carnacki’s darkening rubber-floored lab with its glass-legged table and coldly-glowing neon(?) tubery makes an unearthly and isolated scene, perfect for eldritch trouble. It makes for a good build-up too; C’s first taste of the menace comes indirectly through his apparatus, patterns on a screen and sounds in headphones, uncanny but at a seemingly safe remove. Not until C turns his attention away does he notice the thing’s actual developing presence beside him.

Carnacki seems to have changed the nature of his “defenses” here. In other stories he works with old-school looking stuff: chalked shapes, candles, special water, herbs, bits of bread, with a few neon tubes for reinforcement. Inside his lab he seems to have dropped the ritual stuff and gone all-electric. Maybe a modern environment needs a more modern style of magic?

Is this the pig-nightmare story? “The House of Nightmare” by Edward Lucas White: http://gaslight.mtroyal.ca/housntmr.htm

About the story: If you had ever read Hodgson’s attempts to do female characters, you wouldn’t be upset at him leaving them out. My own theory is that he never actually spoke to a woman in his entire life.

While the deus ex machina is annoying here, in some of Hodgson’s other works, divine intervention shows and fails. For example, in The Night Land, a group of young men being Pied Piper-ed to their doom are suddenly shielded from the forces of evil by a divine-intervention light-barrier. They wait till they can get past the barrier and keep going. I don’t know his personal beliefs but, in his fiction, there was no guarantee a benign force would win out against a malignant one.

Real life pigs can be scary. Guy de Maupassant had a story where a man kept his pigs in his cottage at night. When he dies, they eat his body before someone lets them out. Not exactly Wilbur.

Ellynne@7: that’s the one! Somehow remembered the pig business as worse than it actually was, but memory does embroider.

An element of the story that I didn’t notice when I read it: the stinky alianthus. Nowadays they’re a pest I know well, need vigilance to keep them out of my brother’s garden, and they do indeed smell bad when cut up for disposal. Adds something to the desolation of the setting.

Yeah, “The Dark Land” is hardly a hopeful setting. Perhaps I am being a bit unfair to Hodgson, but if you are a Scientific Ghost Hunter, and the story isn’t going for “everyone dies”, you really should be able to get yourself out of your own messes with science! and clever thinking.

I wonder if crossing the streams would have worked? :)

Lovecraft, for all his acuity in some matters, was unable to grasp that Carnacki, rather than being the ‘infallible’ detective, was far more human and prone to error than the examples he cites. Not only that, but Carnacki expresses degrees of common annoyance and genuine ‘funk’ which are lacking in many of his counterparts. John Silence, in comparison, is a rather too clever-clever chap rather over-proud of himself. Not that the stories have no faults, rather that their humanistic strongpoints are missed by many commentators (not talking about this enjoyable article, but a more general tendency). Maybe. Just my pennyworth. :)

Bruce@8, I don’t know if you’re being unfair. It’s a deus ex machina in this story, after all. Hodgson is interesting because, while I love some of the stories he creates, his writing can be so terrible.

In fact, there are parts of The Night Land that could have been written by evil elder gods out to destroy men’s minds and drive them mad. It would explain a few things.

But, really, I don’t know how a writer manages to be so good and so bad at the same time.

Anne — In the case of The Night Land, I’d say “nauseatingly sticky romantic sentimentality” is a pretty accurate descriptor. Our Nameless Hero, in the framing story, falls asleep and wakes up millions or billions of years in the future after the sun has gone out and the world is infested with terrible forces, and he sets out on a quest across the Night Land to rescue his sweetheart, who has also been reincarnated into this world; and the only word I can think of to describe the way their relationship is described is “treacly”.

(Plus, to quote the clerk at Uncle Hugo’s, you get the feeling that the entire gigantic book was written solely so that Hodgson could ultimately have Nameless Hero and his sweetie bathing naked together in a clear pool.)

Hodgson couldn’t write romance or women. No argument on that point. If you enjoy The Night Land, you enjoy it for the world it creates (if “enjoy” is the right word for the last of humanity living in the last, inevitably doomed fortress in a world of soul-eating monsters).

There’s also a rather odd insistence to it (especially given that Hodgson definitely has a quirk or two) that if you know about romance, you’ll know that it’s just like this.

“My own theory is that he never actually spoke to a woman in his entire life.” In fact he was married, and also had a sister.

Lovecraft on The Night Land: From a letter to August Derleth, 6 November 1934:

“Well — I’m a couple of hundred pages into “The Night Land” — but it’s damn hard going. God, what a verbose mess. And yet the chronological-geographical idea & some of the macabre concepts are magnificent. Don’t know whether I’m going to side with you or with Klarkash-Ton in the end. The pseudo-archaic English is an acute agony — a cursed hybrid jargon belonging to no age at all! That’s Hodgson’s weakness — you’ll note a sort of burlesque Elizabethan speech supposed to be of the 18th century in “Glen Carrig”. Why the hell can’t people pick the right archaic speech if they’re going to be archaic?“

Of potential interest: Hodgson versus Houdini.

I never did say it was objectively a good story. It does feel a bit like he didn’t know how to get Carnacki out of that mess using Science… but he was a recurring character, so he couldn’t just fall into a pig pit. Might have worked better if he lost Baines, though.

My weakness for mad science rants is going to end up like that one semester where a student used a kitten to illustrate operant conditioning–and once the other students saw my reaction, all their presentations suddenly ended with a random picture of a baby animal. (The kitten was reward, not subject. Cats don’t respond as predictably to reward and punishment as you might expect.)

Hodgson and women: it’s remarkable how many people with wives, sisters, and mothers are still able to give the impression of never having talked to a woman. Then again, some people with well-documented friends and relatives can’t write decent characterization of humans at all. I suppose it’s the same issue as with figure drawing–overcoming assumptions and scripts, well enough to see what’s in front of you, is a perennial challenge.

FWIW, I found Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’ much more readable than The Night Land, and if not as nightmarish, parts of it were still pretty unsettling.

James Stoddard (whose High House trilogy is essentially a love letter to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series) actually did a complete rewrite of the Night Land, in an effort to convert the language into words in arrangements such as might be used by actual English-speaking humans. And there’s a surprising amount of Night Land fanfic out there, some of it really quite good.

Boats of the Glen Carrig is great up until they get aboard the weed-stranded but still manned ship and the subsequent Treacly Encounter takes way too much of the tension out of the story.

@15: that’s fairly rich coming from a man who kept making eye-rolling efforts to transcribe dialect in every third story or so. :)

@15/18: The line that jumped out at me was, “God, what a verbose mess.” Although, to be fair, despite his thesaurrhea, HPL could be reasonably succinct (unless he was writing about architecture), especially when compared to Hodgson.

And while his dialects tended to be pretty bad, what’s upsetting him in Schuyler’s quote is bad archaic language. That’s the sort of thing you’d expect him to know and get right and seeing it done poorly would drive him nuts. God knows what he’d make of the sort of horrible faux-archaic you hear today, where people don’t know how to use and decline thou and think ending every verb with -th makes it old.

@17: I think I like The Night Land more for the fanfiction than the original. Hodgson did some fine world-building there, at least, and brought out the best in some other dreamers. (Some favorites in the stories section of http://nightland.website/index.php)

In some ways TNL seems like an extension of the Carnacki mythos: the far-future descendants of C’s haunters, grown huge and fantastic in the unending night and held back only by what looks very like a far-future descendant of C’s neon-tube defences.

Any time somebody uses pigs for horror, I always think of a short story I read where it turns out the serial-killer-main-character disposes of his victims’ bodies by feeding them to his pigs. I don’t usually think of pigs as being scary, but those were the scariest pigs ever put to page, I swear.

@5: The only clip I’ve seen from that movie was of the moment the mother sees the pig thing looking in through the upstairs window. I have this weird fear of things looking in through my window at night, so that gave me a major case of the creeps.

I started Hodgson through Carnacki and the Night Land, which was probably a mistake because those are his weakest stories, It took years before I bothered to read anything else of his. Wikipedia has a collection of some of his short stories, as well as his “trilogy” of poor sods accidentally encountering the infinite. Carnacki and his “professional occultism” are actually outliers. While the protagonists aren’t stupid, they lack the knowledge of chemistry or astronomy or ancient forbidden lore that Lovecraft’s protagonists have. This helps speed the story forward.

The thing I most like about the Carnacki stories is an aggregate quality rather than of any one of them – that they sometimes feature supernatural forces and sometimes not – and sometimes both a hoax and something supernatural is happening. It’s a rare uncertainty to be able to go in with.